Farewell to Hamill

Skint Julep | September 2020

Hamill was dead and there seemed nothing really to do about it except smoke a cigarette in the midnight heat.

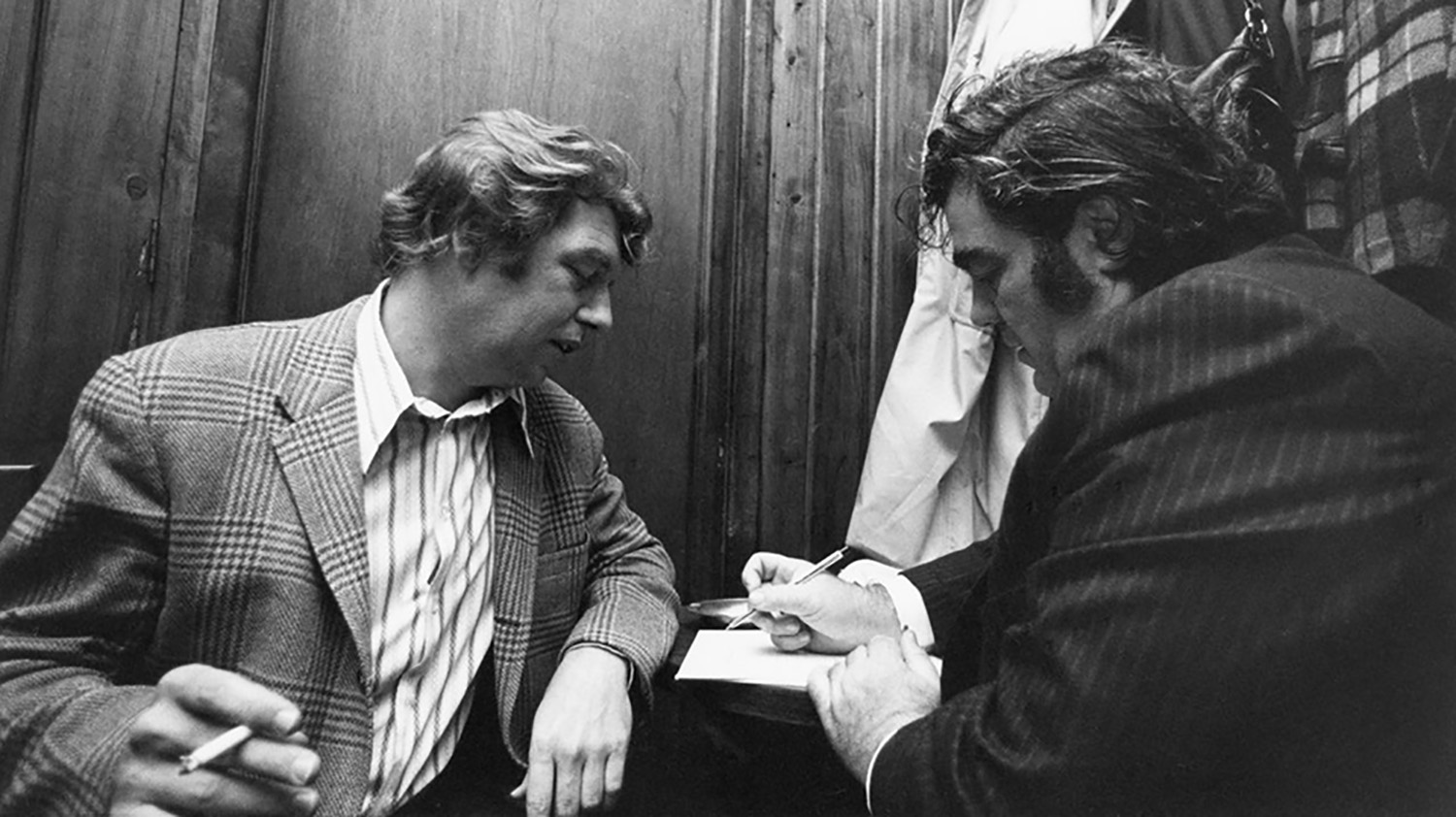

You don’t run across men like Pete Hamill often. The world lucks upon them once in only a great while. Not just a brilliant, crusading journalist, editor and celebrated writer and essayist, Hamill was a mensch. He was a man in full, of his time, and a chronicler of his era and the city he loved. He loved booze, women, song, cigarettes, too — those “goddamned cigarettes” he took to referring to them after he had finally quit — amid the clattering hum of 1960s New York newspaper newsrooms before he found some of these vices inhibited his instincts as a reporter.

All this made him not just a notable New York journalist, but a boldface name, seen in the company of Jackie Onassis, Shirley McClaine and Linda Ronstadt, among others. His rugged good looks and sharp, inquisitive mind made Hamill, unlike his contemporaries Jimmy Breslin and Mike Royko, even Norman Mailer, not just a celebrated journalist and columnist, but a bona fide celebrity. By any definition, Pete Hamill was a renaissance man.

As soon as I could, I read all of Hamill I could fine. Before the internet, I delved into microfilm copies of New York newspapers at the library or picked up copies of the Daily News and The Post for his column in airport newsstands, watched him on news programs and followed his career. I read his books — “A Drinking Life,” his memoir of life in the 1960s and ‘70s, and “Tabloid City,” an engrossing newspaper thriller, my favorites, but also his tribute to Frank, “Why Sinatra Mattered.” His other novels, a mixed bag, review-wise, but which I also think I’d enjoy, I’m leaving for a period of incapacitation. That would make Hamill smile, I think.

I identified with Hamill because Hamill identified with, and was sometimes a contemporary of writers, artists, politicians and celebrities I admired, from Hemingway to RFK to Francis Albert. There’s a book in there titled, “Why Hamill Mattered,” because he did. The man won a fucking Grammy for writing the liner notes to “Blood on the Tracks.” All of this mattered. When I also learned he was first a graphic designer before wandering into a try-out at The New York Post that established his career, that more than sealed the deal for me.

Growing up in suburban 1970s Chattanooga presented an illusion of a bucolic, idealized America both removed from and deeply besotted with institutional racism, poverty and corruption. City leaders today like to say the place once cited by no less than “the most trusted man in America,” Walter Cronkite, as the dirtiest city in America is now … well, not. It is prettier, more attractive to young families and professionals, dotted with franchises associated with the upscale and the upwardly mobile, and that progress shows. But it still struggles, and that shows, too. At its heart, it’s still a crossroads of logistics, with a few good bars and too few talented people, not an oasis of any kind. As in New York City, myth and memory, the last coins of the realm of an old guard, die hard here.

Back then, Chattanooga, a smallish mid-size city propped up by an industrial base that lurched economically and sputtered pollution and was, in all respects, nowheresville to a teenage kid with journalistic, artistic and literary ambitions fed by the likes of Rolling Stone. It was rich in scandal and decay worth documenting on a daily basis in the newspaper, but such stark issues were also good reasons for any young person who could to exit as soon as possible.

My quiet, white-flight hamlet and the larger, mostly boarded-up downtown and largely underdeveloped Hamilton County in the shadow of a new nuclear plant was served by two daily newspapers: the more crusading, the Democrat-leaning Chattanooga Times and the tabloid-ish, right-leaning News-Free Press, whose very name exposed its core mission. It was published in poorly reproduced color, often with splashy tabloid inserts and columns of little substance. The Times, by contrast — founded by Adoph Ochs, also the founder of The New York Times, was run by his descendants and relations — presented to me, even at a young age, a more fact-driven, responsible daily newspaper. I read The Times and aspired to be a newspaperman like Hamill, even though I had yet to learn about him if only I could figure out how. He did, and so did I.

As a precocious young man, imbued with a keen, obsessive curiosity that not long into the future would lead me out of this town, I could not have then so easily discovered Hamill. I knew of Breslin and Royko because both had published collections of their respective work as crusading columnists beloved by readers in their hometowns of New York City and Chicago. I devoured those collections avidly, often piecemeal in the thin aisleways of the Waldenbooks at my local mall. Royko and Breslin were featured on “60 Minutes” and their columns syndicated, they were sought-after journalism celebrities, not unlike Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward. Hamill was then and remained a New York City institution, known by all there but not outside the city.

Instead of Hamill, like many a ‘70s teenager with an attraction to journalism and politics, I found Hunter Thompson. Into the heady mix of Watergate-meets-rock-and-culture-wars, Thompson stepped and was hard to ignore, impossible not to notice, really, an intoxicating personality and a rock star writer before there were any. And there he was, on the cover of Rolling Stone, cigarette holder, cocktail and gun in hand, daring me to buy the ticket, take the ride. And I did, wholeheartedly. I was not alone. But I was not alone enough to attempt to make it known that I was no ordinary kid. I presented one of my first high school book reports in front of a class on Thompson’s “Great Shark Hunt.” I played in rock bands, traveled with the undesirables, the “hoods” we called them then. I wrote about sports for my high school newspaper without really reporting on the game, other subjects with a cynical eye as it struck me Thompson might, but not what one traditionally found in a high school rag. We drank too much for teenagers, smoked too much and stole diet pills from Eckerd’s at the mall to keep going, partying too freely and without consequence. I found in that particular youthful decadence and delinquency, this middle-class privilege, a false identity and assumption of intelligence and better-thanism that relied more on my broad reading than actual education. Or experience. It took me a long time to gain some of both.

And it took years for me to discover Hamill, and then only because I traveled in circles of older, wiser journalists because I was older, if not necessarily wiser, and had traveled and grew professionally in my own newspaper journey. Like Hamill, I also pursued a haphazard career before finding my footing, first in the service as a military journalist, then as a graphic designer and writer, abetted by some talent and a lot of luck and bold, naked ambition. But when I did, it landed upon me with a thud that my original idol was false, at least in how I began to view the world. Thompson never found a home in daily newspapers; not for lack of trying, rather his style was unsuited for journalism. In his lifestyle, he found his true calling on the page. It was startling, outrageous and thrilling. But Hamill was the real deal for me — all the things Thompson was not or seemed to be, but who had put youthful flailing behind him in pursuit of serious work. It was not so much a revelation, since by the late 1980s Thompson was an even more cartoonish character, and because he was no longer a trailblazer in the New Journalism he helped establish. Elevating myself up and out of my circumstances exposed me to new cultures, new cities, new people that led to exciting new discoveries and ideas, new writers and reporters of consequence, Hamil among them. Like him, but never as smartly, or talented or as ambitiously, I evolved and flourished in my career.

I mourn and celebrate Hamill. Because he lived a long, full, colorful life worthy of admiration and reflection, a treasure of a man, a journalist, an editor, and writer of conviction and purpose. And least of all because I am, after all these years and 20 years Hamill’s junior, a man out of time. Many voices far more worthy than mine can testify to Hamill’s impact, and have. My own begins by adapting the lede, even the headline, of Hamill’s eulogy to Bob Fosse in The Village Voice. It is an expression of my admiration of Hamill and in tribute to him. He made an impression that bridged New York City to Chattanooga and beyond. He will truly be missed.